Playwright and Reviewer Gap

For most plays there’s a gap between what the playwright intends and what the reviewer receives. For CHINA DOLL the gap between intent and reception has been unusually wide. Even though some reviewers cried “obvious,” they didn’t glean the less than obvious contributions toward the theme of Mamet’s play.

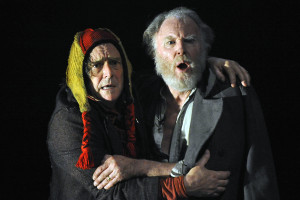

It seemed to many that CHINA DOLL is just a one-sided parlor drama in which David Mamet forgot to include other characters and wouldn’t let Al Pacino’s character get off the phone. They missed the machine-gun dialogue they’d come to expect from Mamet. They wished for the things ordinary Broadway plays have.

Maybe someone can answer this. Do reviewers really not understand the plays they don’t like? Or is it aggressive helplessness? Faux-floundering that condemns in the safest possible means? “I just didn’t get it.” Rather than debate a sociological theme or psychological insight that a play like CHINA DOLL has put forward, reviewer haplessness puts the blame squarely on the playwright.

If this is true, why? Maybe it’s because dismissing a play as horrible is easier, less dangerous and dirty, than debating. Attacking a play for its look and feel risk nothing. Posing an argument is dangerous for some, beneath the dignity of others. An argument reveals too much and no one in good taste reveals too much. Better to attack the surface, the “touchy feely” aspects, of the production. Many reviewers seem furious that CHINA DOLL isn’t pretty. Trouble with opinions is that when they appear in print they masquerade as facts. The reviews say CHINA DOLL is horrible, therefore it must be a fact. Jonathan Mandell of the DC Theatre Scene comments:

David Mamet’s CHINA DOLL involves two dramas. There’s the one on stage starring Al Pacino as an old billionaire in the something of a cynical primer on wealth and political ambition. Then there’s the pile-on against the show: The reviews have been the worst anything on Broadway has gotten this whole year. [. . .] With only a few exceptions, the reviewers have sounded hostile, one calling the play “garbage.”

Recent Comments