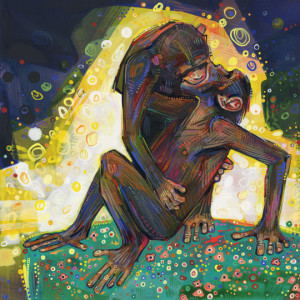

Bonobos in THE QUALMS by Bruce Norris

Bonobos are first mentioned more than halfway through THE QUALMS. Party host Gary says that humans are genetically engineered for warfare. His partner Teri says, “That’s not true. What about bonobos?” Gary continues, “—look at chimpanzees. Chimps conduct strategic attacks on rival tribes.” After the others protest, he adds, “—to protect their territory.” Then Teri says, “But Gary, Bonobos resolve conflict through sex instead of aggression and we’re genetically closer to bonobos.”

This déjà vu bonobo lesson got my attention. It was so similar to the bonobo and chimp parable in David Grieg’s THE EVENTS. [Bonobo Part 1: THE EVENTS] In this instance, however, there was cause to believe Bruce Norris would go further. And he does. His subject in THE QUALMS (Playwrights Horizons May 2015—July 2015) is closer to what has so intrigued us about bonobos, their use of sex to resolve conflict.

The play’s setting is a beach community condo owned by Gary and Teri where four couples have gathered, in theory, for erotic partner swapping. Newcomers Chris and Kristy struggle to fit into the “lifestyle.” Chris, in particular, can’t get past his hierarchal orientation.

His insistence on class distinction is cleverly symbolized by his bringing an expensive bottle of cabernet to the party. Inevitably the red wine and associations with spilt red wine contribute to the crisis.

BONOBO AND CHIMP ZOO CHATTER

Bruce Norris is the author of a dozen or so unsettling, naturalistic comedies, including the Pulitzer Prize winning Claiborne Park. Many like THE QUALMS originated with Steppenwolf Theatre Company.

In his introduction (Playwrights Horizons Preview Editions), the playwright undersells THE QUALMS with a dry sociological account of the play exploring class competiveness. Sure, there’s that, but without question the eight characters interact as archetypal party animals. The audience is encouraged to view the beach condo scenario as a human zoo exhibition.

There is a frequent wonderful effect of five or six of the characters talking at the same time. In print these chatterings are formatted in short columns across the page. Each chattering marks a significant juncture in the group dynamic with a cascade of character views that advance the insecurity and tension.

For most of the ninety-minute continuous scene, the males exhibit aggression, vying for attention with a variety of displays: status (Chris), intellect (Gary), anger (Roger), and physical beauty (Ken). The females (Teri, Christy, Deb, and Regine) have their hang-ups too but are more interested in bonding with one another for the overall success of the party. And in the end, violence is quelled with, yes, bonobo-style conflict resolution. The bonding of the females outweighs the competiveness of the males. The “girls” demand love not war, food-sharing instead of fist fighting.

A key moment occurs early when plus-size Deb enters with banana pudding and encounters condescending Chris. His attitude toward her and her contribution to the party—after all he has brought a hundred and fifty dollar bottle of cabernet—is central to the tension in the room. Deb and the others reject his offering, it turns out, because of a past incident of red wine spilt on the white carpet in the bedroom. No one wants to repeat this goof, but Chris won’t let go of his cabernet as a prestige enhancer.

His inability to move on suggests a source for violence, pointless rigidity. And the spilt cab on the white carpet calls to mind bloodshed on a battlefield. As Deb puts it, “Red wine. Boo.” There is a funny bit halfway through about whether or not there is an alpha male in the room. Gary hints that Roger is behaving like “the silverback.” Roger rejects this notion: “The fuck is he talking about?” Chris ignores recent history, and current events, by advocating that humans have evolved beyond that kind of behavior.

Teri foreshadows her bonobo credo (and its probably source) by admitting that she once watched Animal Planet for eleven straight hours. “Nobody likes angry people,” she says. She tries to diffuse the troublesome conversation through out the party. Three-quarters in, Teri senses the interaction has gone down the wrong path and that Chris is being picked on. She tries to stop it. She campaigns for the revelers to eat more food, as the crisis of Chris sexually rejecting Deb, a polyamorist no-no, approaches.

At last Kristy (Chris’s wife) lays out their true motivation for being there. She tells her offending and jealous husband. “The only person I was ever attracted to was her [Teri], okay? Same as you.” She accuses Chris of turning it into a contest and things go from bad to worse.

BONOBO PEACE TALK

The violence in THE QUALMS amounts to one shove. The stage directions are firm.

With one shove—and nothing more, note to enthusiastic fight choreographers—KEN sends CHRIS stumbling backward, landing on the table loaded with food which topples under his weight, sending dishes everywhere. In the ensuing melee, GARY restrains KEN. ROGER remains seated, cackling at the chaos.

Teri screams that she won’t allow violence in her house. Then she hurls the bowl of condoms across the room. “No!!! I’m so fucking sick of men with your bullshit how you have to ruin everything.” She takes charge, as if she were a senior female in a bonobo troupe.

“Just because there’s a pretty girl that you all want to sleep with, that’s why you have to go and ruin everything so now no one gets to have sex with anyone and I don’t even care because you’re so disgusting and mean and I hate it and I want all of the men out of the house right now.”

Order restored, Kristy starts cleaning up and then they all clean up in silence for what seems like five minutes. Competition has morphed into cooperation. During the thick, luxurious silence, there is more beauty in their quiet shame, their humble work, then in all of the posing that has come before. When they talk again, it’s shy confessions about losing their virginity. This spurs Teri to go into her personal sex history. Her story begins with getting pregnant at sixteen and running away from her conservative parents to have an abortion. The procedure funded by the sale of her grandmother’s wedding ring.

The eight characters agree that humans are promiscuous and then break the fourth wall. They stare out at the audience and see themselves, as if looking into a large mirror. And the audience now understands that the characters are reflections in a mirror too. The ape mirror. THE QUALMS ends with the group eating the banana pudding, Deb’s party contribution, out of the same bowl, the most bonobo moment in the play.

LITERALLY SWINGERS

If anything THE QUALMS demonstrates that humans at a sex party can flare up and cool down like bonobos. The play doesn’t end with an orgy. It might have given more time and tolerance from the audience.

In Bonobo and the Atheist, Franz de Waal refers to bonobos as Kama Sutra apes, for their creative sense of sex. He goes on to say that he has seen captive bonobos do it in every imaginable position, even some positions hard to imagine. Like while hanging upside-down by their feet. This, I guess, gives new meaning to our term for the sexually-adventurous. Swingers.

De Waal, the foremost authority on bonobos, sometimes encounters QUALMS–like polyamorists after his lectures. He says that he has learned to be wary of these folks and their eagerness to assimilate with the ethics of our kindred species. He shies away from their bonobophilia. Drawing from limited knowledge, these bonobo idealists propose that humans become matriarchal and sexually open to end violence. They ignore, as De Waal notes, that humans and bonobos have evolved very differently.

Monogamy isn’t perfect and the divorce rate is high. But when it works well male humans share child-care responsibilities. This is virtually unknown among males in the ape world because a sense of fatherhood is diluted when females have multiple sex partners. Humans associate desire with love and procreation. Bonobo sexual behavior serves non-reproductive functions. It includes greeting, conflict resolution, and food sharing. De Waal comments:

[. . .] the more one watches bonobos, the more sex begins to look like checking your email, blowing your nose, or saying hello. A routine activity. We use our hands in greetings [. . .] bonobos engage in “genital handshakes.” Their sex is remarkably short, counted in seconds, not minutes. We associate intercourse with reproduction and desire, but in the bonobo it fulfills all sorts of needs. [ . . . ]

In other words, for humans to be able to use sex as bonobos do for conflict resolution, we would have to completely alter what sex means for us. And in so doing, alter our identity as a species. Being more like bonobos would include engaging in sexual activity from the time we are infants. Researcher Vanessa Woods has made a comparison of ape orphans in the Congo. She found that bonobo infants engage in sexual contact at moments of excitement, such as when they are being fed. Chimp infants don’t. The species difference shows up early in life.

Still, the value of a play like THE QUALMS is that it shows, for all our differences, we can learn from bonobos. We may never be ready to adopt their utilitarian use of sex, but there is room for compromise. De Waal suggests that we are bipolar apes. “On our good days, we are as nice as bonobos can be, while on our bad days, we are as domineering and violent as chimps can be. How our common ancestor behaved remains unknown, but bonobos offer essential insights.”

What about you? Have you encountered bonobos in the theatre? What do you think? Is there a middle ground? Can bonobo ethics save us from ourselves?

Leave a Reply