David Mamet, WHO is CHINA DOLL?

In the smart new Mamet play, who (or what) does the title refer to? A great question! Unless I’m mistaken, the words “china doll” are not spoken. I took it that the title refers to the girlfriend Francine Pearson. Or, more precisely, Mickey Ross’s perception of her. How Ms. Pearson “appears” in his psyche. How he has fashioned her in his mind.

In the first act of the play, Ross lays it out in simplistic terms. Francine didn’t marry him for looks or for youth. She married him for money. He never factors in that there are subtle factors for which a person might marry. He tells Carson that a beautiful woman will always be able to entertain many offers and she will simply choose the best offer. Ross beholds Francine as a beautiful and brittle object. She is a figurine needing his protection, a valuable chess piece for him to move around his psychic game board.

In Beckett’s important work Endgame, Hamm’s first words are “Me . . . to play.” In CHINA DOLL, Mamet dramatizes the final moves of Mickey Ross, the play’s Machiavellian anti-hero.

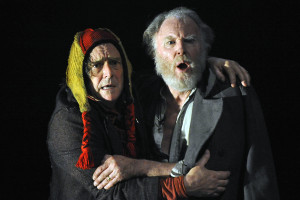

Fool (Richard O’Callaghan) and Lear (Tim Pigott Smith in The West Yorkshire Playhouse’s KING LEAR. In CHINA DOLL by David Mamet, Ross is Lear-like for his rage and folly.

Hamm (George Roth) and Clov (Terrence Cranendonk) in Endgame produced by the Cleveland Museum of Art (2011), photo by Peter Jennings. Beckett’s Endgame is the absurdist model for CHINA DOLL by David Mamet

Ross and Carson ( Al Pacino and Christopher Denham) in CHINA DOLL by David Mamet at the Schoenfeld Theater (Photo by Jeremy Daniel)

AKA Ann Black, in this Mamet Play, Chess Piece? Conspirator? Spy?

And because his fiancé doesn’t appear in the play, we are invited to imagine her at the end of a phone call. An Aphrodite of our minds. Even there, her imagined presence offers more than Mickey’s picture. The false name that she uses in the hotel in Toronto, Ann Black, is telling. Miss Pearson is more than she appears.

“Black” may refer to her chess piece color and hint at darkness and subterfuge, a hidden agenda. She doesn’t explain why she used a false name when he asks her. Ross doesn’t press her for an answer even when it becomes clear that his legal problems may have nothing to do with tax evasion.

He is told more than once that his problem isn’t with the governor and the sales tax but with a federal conspiracy charge (to corrupt a foreign government). He rejects this because it doesn’t fit with his chess game scenario. “The feds don’t have a horse in this race,” Ross says. In other words he doesn’t see them as “horses” or “knights” in the chess game he thinks is between him and the governor.

The first name of the girlfriend’s alias, Ann, is well chosen for its simplicity. To me, this name in the context of a queen chess piece calls to mind Ann Boleyn, Henry VIII’s willful young queen, his second wife, who did not fit into his game and was beheaded. Ann Black in Mamet’s thematic scheme suggests a dark queen of intrigue. She is more than what meets the eye.

“I Don’t Fly Commercial”

The important phone call that Ross has with Francine begins with him telling her that the new jet they own is temporarily unavailable. She is going to fly on a commercial airline for their rendezvous in London. He then reacts to her telling him that she doesn’t fly “commercial.” In other words, she doesn’t fly with commoners. Here Ross goes into his attempt at humor, grotesque patronizing.

As if speaking to a naughty child, he reminds her, facetiously, of finding her penniless and barefoot in Trafalgar Square. He jokes of buying her from gypsies. He says he saved the receipt. Pacino’s tone as he was delivering these lines is of one who thinks he’s being charming even as he is reminding her of his financial leverage over her.

He sounds like a rich old fool in love with a young woman in commedia dell arte. Ross is never the mouthpiece for Mamet, as some reviewers have held. Rather he is a billionaire example of a blind old fool and a bane to society. As Kent puts it in King Lear, “When majesty stoops to folly.”

Mamet Structure in CHINA DOLL: Eavesdropping on Phone Calls

Most of us have overheard, at a distance, intriguing phone calls, when as eavesdroppers we filled in the gap of what was happening on the other side. The plot advances in CHINA DOLL mostly through strung-together phone calls that invite the audience to imagine the people on the other end. (It’s a bit like being a kid again and learning things about your parents from the personality changes they take on while on the phone.) When Ross employs his boorish humor and says he bought a new jet because the ashtrays were full in the old one, we imagine the look on the face at the receiving end.

To me this latest play by Mamet is often more interesting, than it is entertaining. As someone who has written plays, I admire the way the dramatist can shift through the gears of realistic speech, the jumps in thought. And Pacino can still work himself up into a textured rage. The most fun I had in CHINA DOLL is Ross going over the top as if he were King Lear.

At the end of Act 1, Mickey Ross fumes over Francine being taken off a plane and strip-searched. He is convinced that they are using her to strike at him. Rationale again that calls to mind his chess game. He never arrives at the more likely scenario, the unspoken Mamet subtext. They are strip-searching her for reasons that pertain to her. And her use of a false name.

David Mamet Weather: A Twister in a Trailer Park

At last he reads the newspaper that Carson has brought. In it there’s a profile article about the governor who is trying to establish ties with his constituents by targeting “malefactors of great and unearned wealth.” Ross learns with disgust that the governor—referred to as “the kid” because he is the son of the former governor—had worked his way through school as a teenager bagging groceries and parking cars. He calls him, “little cocksucker” for having this earnest beginning to his resume. Ross’s contempt here is important because it goes without saying that he didn’t work at these kinds of jobs as a teenager. Work has been beneath him his whole life. Ross mocks “the kid’s” education by saying that all he thought they did in those ivy-colored halls was learn to make scented candles. Ross attitude is summed up by Shakespeare’s aphorism in King Lear: “Wisdom and goodness to the vile seems vile.” (Act IV, sc. ii)

Ross questions the governor’s claim of following in his father’s footsteps and living a life of public service. “Then how’d he get rich?” During this long layered phone call with their mutual colleague Dave Rubenstein, Ross speaks to the governor indirectly through Rubenstein. He threatens the governor with some bad weather. “You fock with me there’s going to be a twister in a trailer park. You fock with me.” This is Ross puffing himself up into god-status and threatening with Zeus-like powers to destroy the lives of poor people. The twister is directed at the governor’s constituents.

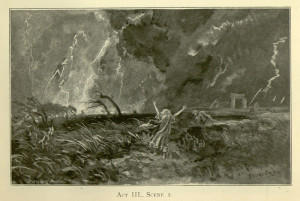

Storm scene in King Lear at the Lyceum Theatre 1892. Promotional brochure, Souvenir illustrated by S Bernard Partridge and Hawes Craven. Parallel to fury of Mickey Ross, China Doll by David Mamet

It is a tornado spun out of his need to protect the china-doll girlfriend. Here we have the tallest moment in the play. Mamet’s poetry is rough-hewn, grand, and mean—the kind of bluster from the delusional men that Mamet has built his career on. I’m reminded of Hamm’s joke in Endgame: “The larger the man, the bigger the emptiness inside.”

Moments later Ross goes into an ancillary rage at the thought again of Francine being strip-searched. He has worked his way up to her being “physically abused” by some matron. He adds the grand finale to the phone call by telling Rubinstein that he will have an asterisk put by the governor’s name in the record books. What is an asterisk? He explains: “the small pointed star that means disgrace.” Ross threatens to bring “so much shame and disgrace” to the governor “that his children will change their names.”

What amounts to a long and ferocious threat is beautifully constructed. First Mickey Ross works his way up into a Lear-like rage invoking nature to rise up on his behalf. Then he threatens the governor with something closer to the heart. Estrangement from his children. This going from the immensity of nature to the very personal is Mamet echoing Shakespeare. As Lear says at the end of his tirade against Goneril, “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth/ To have a thankless child!”

For more on CHINA DOLL, click on this link for my first Mamet post. Thank you for your wonderful comments for Mamet Part 1.

Leave a Reply