THE PLAY THAT SHOWS NABOKOV’S EARLY GENIUS

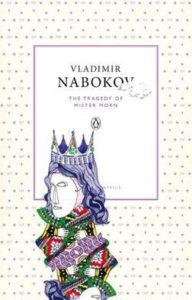

Vladimir Nabokov’s first major work, THE TRAGEDY OF MR. MORN was written in the winter of 1923-24 in Prague when Nabokov was twenty-four. After completing the play in January, he wrote in a letter he felt like a house just emptied of its grand piano. And what a grand piano it is, full of music and wonder.

Two years later he wrote Mary, the first of nine novels written in Russian. Other Russian novels include King, Queen, Knave (1928), The Luzhin Defense (1930), Glory (1932), Laughter in the Dark (1933), Despair (1934), Invitation to a Beheading (1936), and The Gift (1938).

Having already fled Russia and Germany, Nabokov became a refugee again in 1940 when he was forced to leave France for the United States. In the U.S. he taught at Wellesley, Harvard, and Cornell. He began writing novels in English with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight in 1941. He followed up with Bend Sinister (1947), Lolita (1955), Pnin (1957), Pale Fire (1962), Ada (1969), Transparent Things (1972), and Look at the Harlequins (1974).

On the Modern Library list of best 100 novels written in English, Lolita is number four and Pale Fire is fifty-two. Vladimir and Vera Nabokov were married for over fifty years and they had one child, Dmitri. In 1961 the Nabokovs moved to Montreux, Switzerland where he lived until the end of his life in 1977.

THE TRAGEDY OF MISTER MORN is set in an imaginary country, part fairy-tale kingdom with an atmosphere like Shakespeare’s Verona or Venice, part post-revolutionary Russia. Before the action of the play begins, a mysterious and benevolent king has ruled anonymously, behind a black mask. Four years ago this king quelled a rebellion and has restored peace and prosperity to a troubled land. The leader of the revolution, Tremens, remains free though his friends “suffer in black exile” because the king views Tremens as a magnet for “the scattered needles, the revolutionary souls” who can be gathered up.

One such soul is Ganus, who has escaped a labor camp and returned to the city, though cured of his lust for rebellion. Through his wanderings he has seen the country’s strength from “four years of radiant peace” and surmises that “to rebel is criminal.” In the opening scene he is motivated by love and hopes to reunite with his wife, the captivating, fickle Midia. Ganus fears she has strayed and tells Tremens,

The wind in the reeds whispered to me of adultery.

Tremens’ daughter Ella is friends with Midia and agrees to take Ganus with her to a party at Midia’s that evening. The plan is to disguise the exiled husband as an actor who has played Othello in a school performance. At the party Midia, Klian (poet of the revolution and Ella’s boyfriend), Dandilio (a blithe philosopher), the Foreigner (who may be dreaming the play), and other guests converse about the marvelous state of their city and kingdom where “Ugliness, boredom, blood—all have evaporated.”

Ella and Ganus in black face paint enter to music and dancing. As the party is winding down, Mister Morn arrives laughing. Ella feels jealousy on Ganus’s behalf and observes “that some secret reverberating sound connects Midia to swift Morn.” Soon all of the guests leave except for Morn and Ganus. Drunk, as jealous as Othello, Ganus reveals himself: “For it is I—your husband! Risen from the dead!” He slaps Morn with his glove and they fistfight until Ganus collapses in the corner. Midia has fainted by the window and Morn, while tending to her, says: “We were just playing. . .” Ganus insists that he and Morn arrange a duel, which is no small matter, as Edmin explains to Ganus by whispering Morn’s identity into his ear. They agree to duel by drawing playing cards the next evening.

NABOKOV’S DUEL WITH PLAYING CARDS

In Act II, Tremens hosts the drawing of cards. He tells a very nervous Ganus, “the soul must fear death as a maiden fears love.” For a card Morn predicts drawing what he loves, “the colour red—life, and roses, and sunrises . . .” The suspense proves too much for Ganus, who passes out; though needlessly, it turns out, because Morn draws the eight of clubs. Edmin grows deathly pale and Morn surmises that the paleness is to contrast the black silhouette of his fate. He must execute himself, but not then and there. Tremens doesn’t want a mess in his home, and Morn prefers to shoot himself in his taller house:

The shot will resound more sonorously in it, and tomorrow will come a dawn in which I have no part.

Morn exits, supporting his distraught attendant Edmin. In a soliloquy Tremens boasts cheating Morn of his actual drawn card, the five of diamonds, through sleight of hand, by replacing it with the eight of clubs—“and death peered out of its funereal clover at Morn!”

FINGER ON THE TRIGGER

In Act III, Morn prepares for death. “Let my crown,—like a taut ball kicked aside,—be caught, and clasped in the arms of my young nephew.” The owl-like senators will noiselessly govern while the boy-king grows. Morn will become a ghost. “What a fairy tale shall I leave to the people.” Edmin blames himself. “The chronicles will not forget the weakness of mine.” Morn summarizes his four-year reign as “an age of happiness, an age of harmony.” He says,

Playfully, lightly I ruled; I appeared in a black mask in the ringing hall, before my cold, decrepit senators . . . masterfully I revived them—and left again, laughing . . . laughing.

He begins to pity himself for being undone “in the radiant noon of my life.” He must die for kissing “a shallow woman” and striking “a foolish adversary.” He tosses off his crown and it rolls “across the dark carpet, like a wheel of fire.” Morn’s long speech in the middle of the play, in fact, is a psychological progression of how he loses his nerve.

At the would-be fatal moment he says, “My finger on the trigger is weaker than a worm.” Up against the abyss of eternity, he cowers: “What’s a kingdom to me? What’s valour? To live, only to live . . . Oh God!” He calls Edmin into the room and then can not bear being perceived a coward. He lies. He says he would yield his kingdom and soul all for the love of Midia. He says,

Edmin, don’t love . . . you cannot understand that a man is capable of burning worlds for a woman . . .

They flee together through a window. . . . Scene II of Act III takes place in the same room, the king’s study, but revolutionaries have taken over the land and four rebels are seated there. Klian enters with the “splendid news” that their “merry crowd” has blown up a school and “three hundred little mites perished.” He has written a new ode honoring Tremens as the genius of the revolution.

In contrast to this, Ganus mourns Morn. The only other beside Edmin to know the truth, he understands that by destroying Morn, the king, he has destroyed his country’s peace and happiness. Tortured by guilt, Ganus passes through the melting snow like “one of the saints in stained glass.” He enters and tells one of the rebels, “A hero lived here.”

Tremens tries unsuccessfully to convert Ganus back to his destructive cause and then exits. Meanwhile Ella has a letter for Ganus from Midia that she has read. She knows that “Morn and Midia are together!” and wonders how to convey this. She tells Ganus that she loves him. Ganus, however, has transcended earthly love in favor of “the austere wings, the straight brows of angels.” Ella shows him the letter and he recognizes the handwriting and tears it up. He says he hates this woman.

Begone, you cunning devil! Because of you, I destroyed my homeland.

The rebels, Tremens, and Klian re-enter. The First Rebel admits to fearing the king still, because the king is a dream that has not died in the souls of the people. He says, “There’s nothing stronger than a dream.” Then Ganus comes back to earth and desperately pieces together the torn bits of letter. Once comprehending, with Tremens help, that Morn lives and has fled with his wife Midia, rather than honoring the outcome of the duel, Ganus rediscovers the vengeance in his heart.

Morn lives, God is dead. That’s all . . . I go to kill Morn.

BLAME FOR THE FOUL SPRING

Act IV begins on a “foul spring morning” with Midia at a window, her back to the audience. Morn, Midia, and Edmin have fled south to a rainy would-be paradise where “the palm trees have drooped.” She tells Edmin that she loved Morn’s laughter but “he laughs no longer” and he has fallen out of love with her. Edmin can’t believe anyone could fall out of love with her. He tells her,

Your smile is the movement of angel.

Their sudden embraces are interrupted by Morn’s entrance. Morn, unshaven and dressed in a housecoat, despairs and takes blame for the foul spring, for everything gone mad. Midia does not know, even now, that he was king and thinks, as she has heard, that the king is walled up underground by the rebels. She tells Morn that she is leaving him for Edmin. “Life calls . . . I need happiness.”

She admits to writing her husband, two weeks earlier, with their address (so that he could send a favorite fan to her), but does not know of the full ramifications of this—Morn, apparently confides little in her and has not told her of the duel of cut cards and how he has reneged on his debt. Alone, he predicts that Ganus will

force his way out of the haze of the maddened city, out of the mangled fairy tale, here, to the grey south, into my hollow, humdrum existence.

Edmin feels cold shame flowing through his veins and begs forgiveness to his sovereign. “You betrayed a kingdom for a woman, I betrayed a friendship for a woman—the very same one.” As Midia packs, Morn asks her twice if she is happy now. She admits to feeling surprised that he would let her go so easily and thinks its strange how they had once loved; “it has all gone somewhere.” He tells her that life is a “vast harmony” and “In harmony there is nothing strange.”

Sensing Ganus’s approach, Morn rediscovers his regal presence with Midia packing to leave him forever. She says that she dreamt that beneath his laughter he was harboring a secret and asks him to tell it. He gives it to her as a riddle that has the clue:

the kings of bygone ages inhabited me.

She departs asking for forgiveness. Morn is on the terrace when Ganus enters the room and hides himself. Morn re-enters the apartment and fusses with the flowers in a vase on the table while Ganus aims the gun with a trembling hand. On a petal Morn sees an ant: “Funny: he runs, like a man amidst a fire.” The curtain falls.

THE DEATH OF MR. MORN

Act V. Inspired by the notion that their king gave up everything for love of a woman, the populace mounts a counter-revolution and drives the rebels into hiding. Holed up at Dandilio’s, Klian predicts his fate:

The lead will strike into my brain like a stone into glistening mud—an instant—and my thoughts will splatter out.

He describes fighting for “five terrifying days” against “the hurricane that was the people’s dream” and being hunted through palace and then fleeing with Ella and their child through the secret passage once used by the king. The optimist Dandilio senses no danger and believes the city has wearied of executions now that Tremens has been driven from power. Dandilio has the crown that he has purchased from a looter for a gold coin.

Tremens enters and tries on the crown and puns that he would prefer a “nightcap.” He has heard a rumor that “the very ruler who had abandoned the city half a year ago” had been whacked on the head in his house by a burglar. “But it’s a shame, Dandilio,” he says, “that the imaginary thief did not destroy the imaginary king!” Dandilio perceives that this rumor involves Ganus and Morn and sympathizes with the thief, not the king. “Yes, poor Ganus! He was unlucky . . .”

Tremens fails to understand and Dandilio reveals that he had recognized Morn’s laughter at the parties they attended as the same laughter as the king’s. He is aware too of Tremens having cheated Morn with the wrong card. Tremens wishes he had known the king’s secret identity so he could have shouted to the people:

Your king is a weak and shallow man. There is no fairy tale, there’s only Morn.

While sick and dying, Ella overhears them and expresses disbelief. There are the voices of soldiers in the streets. Four soldiers and a Captain enter the apartment. Klian flees and chaos ensues. Ella, having heard a voice in her sleep, rises up from delirium and announces, “Morn is the King. . .” From offstage comes the sound of more voices and then Klian being shot.

In Act V, Scene II, a merry Morn, merely wounded, is convalescing in an apartment. He has become kinglike again and seems ready to re-ascend the throne. Withstanding the bullet from his executioner Ganus, in effect having allowed the wronged party a clear shot at him, he has paid his debt for adultery and can resume his life without guilt.

At his side are Edwin and a Lady, probably Midia, whom he mistakenly calls Ella. He is happy until an intruder arrives, the same Foreigner who attends the party in the first act, a man who insists he is nothing: “I’m simply asleep.”

Displeased at first, the king changes his tone and welcomes him. The Foreigner remembers the king from his previous dream as being Morn. He remembers also that something wasn’t right there. Morn equates the ramblings of “this spurious somnambulist” as being like the fools of past kings, fools who spoke “the truth darkly.” Slowly he realizes how much of his past life has been a lie.

I appeared now in a mask upon the throne, now in the drawing room of a vain lover . . . Deception! And my flight was the lie, the trick—do you hear?—of a coward!

He compares himself, his life, to a torch flung down a dark well and hurtling downward to meet its reflection “that grows in the darkness like the dawn.” He begs Edwin for his black pistol. He thanks Edwin and goes out to the terrace to end his life. “The blue night takes me away.”

Edwin says, “. . . No one must see how my King presents to the heavens the death of Mister Morn.”

ANALYSIS AND INFLUENCES

Speak Memory: An Autobiography Revisited opens with the words:

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour).

Existence as a brief crack of light is something the prolific author had begun to express as early as 1923 when he wrote several short plays—Death, Granddad, and The Pole—in which characters face off with death. Nabokov scholar and biographer Brian Boyd observes in Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years that this preoccupation continues and intensifies in THE TRAGEDY OF MISTER MORN, as exhibited through Morn, Ganus, Tremens, Ella, Dandilio, and Klian with metaphysical language reminiscent of Hamlet and Claudio’s great speeches. “And yet,” Boyd reminds, “this is a tragedy about happiness.” Within the five acts of MORN “life teems with happiness even in the face of death.”

The word “happy” reoccurs over and again throughout MORN. The title character is preceded by his laughter. He arrives late to Midia’s party where the other guests have decided that he is the happiest in the city. He apologizes to Midia for being late and then asks Ella to dance. After his dance is interrupted by Klian cutting in, a joyous Morn, smitten by life, reconnects with his hostess.

. . . Oh, my Midia, how you do resemble

happiness! No, do not move, do not spoil

your splendour . . . I am cold from happiness.

We are on the crest of a wave of music . . . Wait,

don’t speak. This very moment is the peak

of two eternities .

For its poetic language and dreamlike atmosphere, MORN resembles the tragedies and comedies of Shakespeare, but the yearning and vacillating of the characters suggest the influence of Chekhov, especially The Three Sisters. For the wonderful parlor wit of Dandilio and some of the other minor characters, the play, at times, feels like the comic melodrama Lady’s Windermere’s Fan. Maybe Midia writing a letter to Ganus for her favorite fan, which she has left behind, and this tipping off her location, is the author’s nod to Oscar Wilde. (Both Nabokov and his father read Wilde before MORN was written.) He also was influenced by Flaubert, as Boyd reports, whom he had begun to reread in January 1924. Overall the imagery and wordplay are as powerful as Shakespeare’s without the semantic difficulties of Elizabethan diction.

The strength of MORN is in its characters, their poetic utterances and their chance-like movements. The unusually vibrant character interactions give us a play bursting at the seams with life. The frequent use of windows, mirrors, and paintings—whether as props or metaphors—indicate a story expanding beyond the limits of a finite stage. Skeptics unwilling to admit that a fiction writer as celebrated as Nabokov could also write a play, one on a level with Shakespeare’s work, cry foul; that his departure from traditional cause-and-effect plotting exposes his ignorance to the rules of drama. A website book review of MORN written by Rodney Welch attacks Nabokov’s sense of plotting and thin characterizations. It dismisses the play as a mistake from an author who recognized that he couldn’t write for the stage and began writing novels instead. Michiko Kahutani in his favorable New York Times book review (March 24, 2013) couldn’t resist the jab that the characters resemble “flat Pirandello-esque creatures moved about by the author as chess pieces in a mirror game between reality and art, the actual and the imagined.” (Why not factor in the author’s fascination with the natural world and say the characters are chess pieces that float like butterflies and sting like bees?)

These perspectives ignore what Nabokov was attempting to do with MORN and what he was reacting against. As Brian Boyd wrote, Nabokov disdained the fatalism of tragedy in general, and in particular the “inescapable logic of cause and effect.” He opposed inevitability on behalf of the freedom of movement that he witnessed in life. And he rejected linear plotting on behalf of the characters he wanted to create—dramatic beings that were more than “a cluster of fixed possibilities.” Even the woman Morn blames for his undoing in Act III, Midia, defies expectations. She is described as “shallow” and then in the final pages as “a vain lover,” but Midia’s explanation to Ganus at the end of Act I, about how she fell out of love with him, is pithy and beautiful.

Then you became transparent, a kind of familiar ghost; and finally, faint and translucent, you left my heart on tiptoe. . . I thought—forever . . .

She offers this as a postscript because the action of the scene has played out when Morn and Ganus agree to the duel. Earlier in the party scene Midia responds to Morn’s “cold with happiness” speech with an account of the power in his eyes. She concludes:

. . . I’ll put it this way—

but don’t laugh: my soul has fixed itself

to your eyes, as when in childhood

one’s tongue sticks to cloudy metal if,

for a lark, you lick in the flaring frost . . .

Now tell me, what do you do all day?

In Act IV she leaves Morn because he has stopped laughing and from this she believes that he has fallen out of love with her. This is understandable. Morn has kept Midia innocent of the knowledge, that is, innocent both of his regal identity and of the duel with Ganus that led to him abdicating. Her unhappiness and the attempt to reunite with Ganus and then leaving him for Edmin spring from the lie of Morn’s love for her. She understands instinctively the duplicity of her situation with Morn when she accuses Edmin of being too reserved with her, “as though I were a whore or a queen.” This identity confusion comes from the same waffling with the truth that will threaten the happiness of the kingdom if Morn reclaims the throne.

THE TRAGEDY OF MISTER MORN is a fairy tale without a queen. The bachelor king who rules incognito can only socialize in the guise of his other. For most of the play there is only one parent, the nihilist Tremens. By the end of the play the other parents will be his daughter Ella and Klian. There is no mention in the play of Ella’s mother. At the party, when only Ganus and Morn remain, Midia asks the disguised Ganus if he has known Ella long. Interestingly Midia fails to recognize her own husband in black paint and yet offers an irresistibly dead-on description of the other important female in the play: “A child . . . like wind . . . like a glimmer of water.”

Brian Boyd asserts that Nabokov’s characterization of Ella is “one of the finest things in the play.” Thomas Karshan wrote in his introduction that Ella ranks with Lolita as one of Nabokov’s few fully realized female characters. This, the co-translator surmises, owes to the author’s recent meeting of and falling in love with Vera Slonim, the woman who would become his wife and the play’s typist. That Vera is the inspiration for the character of Ella seems plausible by the spirit of love and humor that this character brings to the play. After his dance is interrupted in Act I, Morn says: “What is happiness? Klian ran past me and, like the wind, took Ella from me.” The implication is that happiness, as personified by Ella, has been snatched from his grasp. Then, just a few lines later, is his speech to Midia about how she resembles happiness. Cold from this species of joy, he instructs her to be still and object-like as to not spoil his viewing of her. In this scene Morn’s coveting of the appearance of happiness (Midia) eclipses his hold on the substance of it (Ella). He becomes what Ganus calls him: “A damned fop.”

Ella’s first word in the play is “Yes,” her response to Tremens’s question, “So you are going dancing?” She exits laughing, a counterpart to Morn who enters laughing. It’s subtle, but Ella is Morn’s feminine alter-ego, his anima, the play’s secret queen. She is the theatre student who knows Othello and speaks as Desdemona. Morn breaks away from Midia, to ask Ella to dance. Ella realizes that she was a fool to bring Ganus to the party incognito (even though the king rules behind a mask). She assumes guilt for this and prefigures the tragic conclusion. She says, “I would give my whole like for this man to be happy.” She pleads for Ganus to leave the party. “I beg you, please also leave . . . You can visit her tomorrow morning.” As he approaches drunken Ganus for the first time, Morn is jealous of the other man’s camaraderie with his dance partner when he says, softly, “Yes, he was plied by Ella.” In Act II before leaving to meet Klian, she feels “Listless languor and a slight chill . . . Is that really love?” This is an echo of Morn’s cold happiness. Ella says, “My face drifts up out of the semi-darkness to meet me, like a murky jellyfish, and the mirror is like black water.” Her dark, despairing metaphor anticipates Morn’s speech near the play’s end when he sees himself a torch thrown down a well rushing to meet its reflection.

At the end of Act II, after Ella loses her virginity to Klian, she feels drenched in “cold pain” because it is sex without love. She remarks that it’s not what she thought it would be. “It’s death, not bliss! My soul has been brushed by the coffin lid . . . pinched . . . it hurts . . .” Her scene partner Dandilio comforts her by comparing life to a young mother who will “fall down upon her knees before the child, and, laughing, will kiss the scratch away . . .” Here Ella is the hurt child who will soon become the young mother. In the second scene of Act III, Ganus asks Ella if she’s happy and she echoes Morn’s definition, “The flutter of wings, or perhaps a snowflake on one’s lip—that is happiness.” She doesn’t recall who said it, a hint of the chasm growing between her and the protagonist.

In this scene Ella combines the political and the personal and suggests a theme for MORN. “Rebellion for the sake of rebellion is both boring and horrifying—like night-time embraces without love.” She tells Ganus she loves him. In her speech to him she combines the love that’s inside her with the entire outside world, “your pale face and the bright tickling icicles beneath the roof,” even the “raw sun.” He remembers not stopping her meeting with Klian as “yet another blind momentary sin.” Sensing his distance, she retreats emotionally: “Really, all is well . . . Days follow days . . . And then I will become a mother . . .” She recognizes that soon a mother’s duty will replace romantic love.

At the end of Act III after Klian says he doesn’t find the time to tell her she’s beautiful, only sometimes in his poems, she answers: “I don’t understand them.” In Act V, while dying, she quotes Desdemona again but doesn’t remember where the lines are from. Dandilio observes that panicky Klian grows calm while watching Ella asleep and dreaming, “as though his fear has gone to sleep with her.” She wakes up enough to overhear her father ranting about, what Dandilio has told him, that Morn and the king are the same. This nearly kills her. She loses her animating spirit. Her father says, “Ella’s like a doll . . . What’s wrong with her?” Her last words in the play are

Morn . . . Morn . . . Morn . . . It is as though I heard a voice in my sleep: Morn is King . . .

In the final scene, as already mentioned, Morn says, “Dancing? There is no room, Ella,” though he is talking to Midia. This is funny, but the suggestion is that Ella is beside him in his thoughts and should be beside him in the flesh if all were going well. The magician king mulls over his life and decides he must die. The seeds of revolution and counter-revolution have come from “his mask upon the throne,” his duplicity as Mister Morn. All of the main characters contribute in one way or another to the sad end, but responsibility must come from the top. Forlorn, realizing all has been a lie, he asks, “Am I really a king? A king who killed a girl?” His failure to rule is his failure to win and to love his counterpart, the play’s true queen.

Leave a Reply