Chekhov and Temporal Complexity in THE CHERRY ORCHARD

On July 2, 1904, Olga Knipper summoned a doctor to the hotel in the German spa of Badenweiler for her famous husband who was dying. After arriving, the doctor ordered champagne from room service for Chekhov. The champagne was to relieve his breathing. Olga reports that he sat up in bed and said in German, “Ich sterbe” [I’m dying]. . . “Then he picked up the glass, turned to me, smiled his wonderful smile and said: ‘It’s been a long time since I’ve had champagne.’ He drank it all to the last drop, quietly lay on his left side and was soon silent forever.”

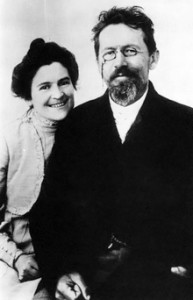

Even with his last words, he was gauging the experience of drinking champagne in a larger context. A long time since. Chekhov was twenty-four when he first became aware of blood coming up from his throat. For twenty years slowly gave way to tuberculosis. During this time he steadfastly downplayed his condition to family and friends. He refused to be seen as a patient. As the author of THE CHERRY ORCHARD, his last completed play, Chekhov immersed the world in the temporal complexity that genius and a life long courting death had made possible.

Donald Rayfield in The Cherry Orchard: Catastrophe and Comedy has written that the subject of the play had a germination that goes back to Chekhov’s childhood. The author spent holidays in the Ukraine among a cherry orchard on a farm. Important too was the deforestation of Russia in the 1880s. And Chekhov himself owned a cherry orchard that was chopped down in 1899 by a timber dealer. Clearly the long-term biographical association of cherry orchards for Anton is important to the construction of his final play.

The Most Shocking Line in the Play

Lopakhin opens the play. It is he that provides the sense of urgency, who must convince the audience of the direness of the situation. He must do this even if Liubov Ranevskaya is unable to give the selling of the estate her full attention. The stage directions ask for him to check his watch frequently. He gives the terrible, impending date of the sale twice specifically (August 23). He refers to it more generally often: “Time will not stand still.” In this regard, Lopakhin is prepared to embrace the portentous future.

Yet, his personal shame at having come from peasantry (“Like a pig in a pastry shop”) and his unease with the advancing new political order indicate that he is stuck in the mud of his private history as much as the other characters are in their own. His hands hang at his sides as if they belong to someone else. By the end of the play when he fails to propose to Varya (fails to ask for her hand), even though this marriage proposal has long been anticipated by Varya and her mother Ranevskaya, we the audience understand that for Lopakhin the conundrum of love and marriage to the adopted daughter of an aristocratic family is as difficult to face as the sale of the cherry orchard has been for the others.

Still, it is Lopakhin that delivers the most shocking line in the play: “The cherry orchard is now mine!” It is a bald statement of a present fact that Chekhov jolts us with. This announcement is like no other statement for its power and immediacy. It leaps off the page. Chekhov has prepared for it by constructing a rich temporal world where talk of the past and future has dominated.

Recent Comments