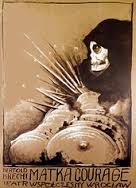

The Influence of J.M.R. Lenz’s The Soldiers on Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children

[This is the seventh and final part of a seven part series. Included is the bibliography for the entire series. Please scroll down to read the six previous installments.]

Theme/Lasting Effect

Lenz and Brecht shared the goal of building a new national audience for drama, and this goal informed every aspect of their dramaturgy. By beginning this thesis with “Spectator Effect” and moving inward, I’ve addressed the thematic dimension of The Soldiers and Mother Courage implicitly all along the way. In this section, I will explicitly probe theme as the inward action that holds the plays together, inspiring and activating a hunger for lasting change in the audience.

The goal of both Lenz and Brecht’s theatre is for the audience to develop into a more class-sensitive public better prepared to begin a dialogue with itself. To paraphrase Herbert Blau: Brecht’s aim for the devices of epic form is to raise the consciousness of the spectator to a higher level of criticism.1 Similarly, Lenz’s aim is to create a tragic audience from a comic audience, as he details in his “New Menoza Review.”2 Lenz wished that everyone, the Volk from all walks of life, would grow up. Yet despite the goals of both playwrights to raise audience consciousness, their protagonists don’t learn anything through which the audience can share a transformation. Both Marie and Mother Courage negotiate their way down unhappy pathways of trial and error and come away no wiser than they were at the beginning of their journeys.

The plays are, in a way, “unfinished.” No hero transformation or direct explanation of theme guides us to unambiguous meaning. The authors’ intents must be deduced. Furthermore, as both playwrights discovered, audience conjecture could contrast sharply with their intents. Even for his well-received The Tutor, Lenz was frustrated by overly literal reactions. He complained that “in some of my comedies people have imputed to me all kinds of moral purposes and philosophical theses.”3 Brecht’s version of this play was seen by East German critics as too negative; and in general his plays, including Mother Courage, were criticized for their pessimistic depictions of reality,4 as The Soldiers was by Enlightenment-era reviewers. Neither playwright believed in the transformation of protagonists as a means to raise audience consciousness, because hero transformation contradicted their anti-idealistic world views and methodologies. And so they suffered the consequences: thematic misinterpretation and confusion.

The Marie Wesener plot of The Soldiers, once Lenz unmoors it from “the true story,” accelerates with lightning-quick speed. The height of Marie’s fall was much more melodramatic than Cleophe Fibich’s. By Act V, her pathway of self-alienation has put her on the street begging for alms in seeming parody of the bourgeois tragedies of Diderot and Mercier and the bürgerlicher Trauerspiele of Lessing. The penultimate scene opens with the stage directions: “Wesener walking by the River Lys, lost in thought. Twilight. A female figure wrapped in a cloak plucks at his sleeve.” (p. 51) The meeting is by chance. Not recognizing that she is his daughter, Wesener rebuffs the woman three times, as if she has solicited sex. How easily she is cast as a “wanton strumpet” by her own father, who seems blocked from knowing her by her fallen status in the class structure. This image of an invisible underclass is an echo of an earlier scene when Marie fails to recognize her fiancé Stolzius because he is posing as Officer Mary’s servant. Marie says: “Tell me, your servant has a strong resemblance to a certain someone I used to know; he wanted to marry me.” (pp. 32-33)

One might well ask whether Wesener ever knew his daughter. In the street scene he is even more deluded by class-oriented assumptions than he is in Acts I and II while placing his trust in the irresponsible Desportes. His third rebuke of Marie contains the play in miniature:

WOMAN: Sir, I’ve gone three days without a bite of bread;

be kind and take me to an Inn where I can have a sip of wine.

WESENER: You wanton creature! Aren’t you ashamed to

make such a proposal to a respectable man? Begone! Run

after your soldiers! (p. 51)

Wessener’s assumption that she must be a prostitute who has given herself over to soldiers, that only this can explain her begging, is a coda to the philosophical quandary that runs through the play. Who is responsible for a woman keeping her virtue? The woman alone? His travails have hardened Wesener to the cynical view Officer Haudy expresses in the first act: “A whore will always turn out a whore, no matter whose hands she falls into.” (p. 11) “Begone” is also the word Countess uses in Act IV when she too jumps to conclusions about Marie. (p. 43) Then something happens. Timothy Pope suggests that Wesener’s failure to recognize his daughter three times is a biblical allusion, Peter’s three-fold denial of Christ, and that Wesener only comes to discover who she is once he regards her as a human being, not as a morally discounted category.5 Scene Four is short but powerful in its economy, symbolism, and thematic resonance. He asks, “Was your father a jeweler?” (p. 51) This simple question reiterates the dual nature of his identity that has plagued him and Marie, the child who might yet become a lady. At last, when the recognition comes, there is tragic parody and then an active response from a crowd: “The two of them collapse half-dead on the ground. A crowd collects around them, and takes them out.” 6 This odd stage direction gives the example of a pro-active crowd, which is fitting preparation for the closing scene.

Recent Comments