The Influence of J.M.R. Lenz’s The Soldiers on Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children

[This is the seventh and final part of a seven part series. Included is the bibliography for the entire series. Please scroll down to read the six previous installments.]

Theme/Lasting Effect

Lenz and Brecht shared the goal of building a new national audience for drama, and this goal informed every aspect of their dramaturgy. By beginning this thesis with “Spectator Effect” and moving inward, I’ve addressed the thematic dimension of The Soldiers and Mother Courage implicitly all along the way. In this section, I will explicitly probe theme as the inward action that holds the plays together, inspiring and activating a hunger for lasting change in the audience.

The goal of both Lenz and Brecht’s theatre is for the audience to develop into a more class-sensitive public better prepared to begin a dialogue with itself. To paraphrase Herbert Blau: Brecht’s aim for the devices of epic form is to raise the consciousness of the spectator to a higher level of criticism.1 Similarly, Lenz’s aim is to create a tragic audience from a comic audience, as he details in his “New Menoza Review.”2 Lenz wished that everyone, the Volk from all walks of life, would grow up. Yet despite the goals of both playwrights to raise audience consciousness, their protagonists don’t learn anything through which the audience can share a transformation. Both Marie and Mother Courage negotiate their way down unhappy pathways of trial and error and come away no wiser than they were at the beginning of their journeys.

The plays are, in a way, “unfinished.” No hero transformation or direct explanation of theme guides us to unambiguous meaning. The authors’ intents must be deduced. Furthermore, as both playwrights discovered, audience conjecture could contrast sharply with their intents. Even for his well-received The Tutor, Lenz was frustrated by overly literal reactions. He complained that “in some of my comedies people have imputed to me all kinds of moral purposes and philosophical theses.”3 Brecht’s version of this play was seen by East German critics as too negative; and in general his plays, including Mother Courage, were criticized for their pessimistic depictions of reality,4 as The Soldiers was by Enlightenment-era reviewers. Neither playwright believed in the transformation of protagonists as a means to raise audience consciousness, because hero transformation contradicted their anti-idealistic world views and methodologies. And so they suffered the consequences: thematic misinterpretation and confusion.

The Marie Wesener plot of The Soldiers, once Lenz unmoors it from “the true story,” accelerates with lightning-quick speed. The height of Marie’s fall was much more melodramatic than Cleophe Fibich’s. By Act V, her pathway of self-alienation has put her on the street begging for alms in seeming parody of the bourgeois tragedies of Diderot and Mercier and the bürgerlicher Trauerspiele of Lessing. The penultimate scene opens with the stage directions: “Wesener walking by the River Lys, lost in thought. Twilight. A female figure wrapped in a cloak plucks at his sleeve.” (p. 51) The meeting is by chance. Not recognizing that she is his daughter, Wesener rebuffs the woman three times, as if she has solicited sex. How easily she is cast as a “wanton strumpet” by her own father, who seems blocked from knowing her by her fallen status in the class structure. This image of an invisible underclass is an echo of an earlier scene when Marie fails to recognize her fiancé Stolzius because he is posing as Officer Mary’s servant. Marie says: “Tell me, your servant has a strong resemblance to a certain someone I used to know; he wanted to marry me.” (pp. 32-33)

One might well ask whether Wesener ever knew his daughter. In the street scene he is even more deluded by class-oriented assumptions than he is in Acts I and II while placing his trust in the irresponsible Desportes. His third rebuke of Marie contains the play in miniature:

WOMAN: Sir, I’ve gone three days without a bite of bread;

be kind and take me to an Inn where I can have a sip of wine.

WESENER: You wanton creature! Aren’t you ashamed to

make such a proposal to a respectable man? Begone! Run

after your soldiers! (p. 51)

Wessener’s assumption that she must be a prostitute who has given herself over to soldiers, that only this can explain her begging, is a coda to the philosophical quandary that runs through the play. Who is responsible for a woman keeping her virtue? The woman alone? His travails have hardened Wesener to the cynical view Officer Haudy expresses in the first act: “A whore will always turn out a whore, no matter whose hands she falls into.” (p. 11) “Begone” is also the word Countess uses in Act IV when she too jumps to conclusions about Marie. (p. 43) Then something happens. Timothy Pope suggests that Wesener’s failure to recognize his daughter three times is a biblical allusion, Peter’s three-fold denial of Christ, and that Wesener only comes to discover who she is once he regards her as a human being, not as a morally discounted category.5 Scene Four is short but powerful in its economy, symbolism, and thematic resonance. He asks, “Was your father a jeweler?” (p. 51) This simple question reiterates the dual nature of his identity that has plagued him and Marie, the child who might yet become a lady. At last, when the recognition comes, there is tragic parody and then an active response from a crowd: “The two of them collapse half-dead on the ground. A crowd collects around them, and takes them out.” 6 This odd stage direction gives the example of a pro-active crowd, which is fitting preparation for the closing scene.

The final scene of the play, the notorious Act V, Scene Five, takes place in the Colonel’s Quarters and involves the two main representatives of the aristocratic order, Count von Spannheim (Colonel ) and Countess de la Roche. (The last scene was rewritten by Lenz at the suggestion of Herder, because it seemed indecent to have the Countess, whom Lenz modeled after the writer Sophie von de le Roche, participate with the Colonel in his radical proposal.) The Countess opens the scene with the question: “Have you seen the unhappy pair?” (p. 52)

This question is also directed at the audience, the observers who have been recruited as co-creators. Breaking down the imaginary wall, the playwright has positioned two characters as audience members who ask: “Have you [the other spectators] seen the unhappy pair?” Like a Plautian aside, it’s an invitation for them to stand back and ponder what they have beheld. From here Colonel and Countess engage in a mock-philosophical discussion of how the problem of enforced celibacy on soldiers and its effect on the local women might be remedied. The Count’s solution that the king found a state-sponsored brothel for soldiers is inspired folly, a parody of the kind of programmatic solutions from the aristocratic order that are rarely enacted and never solve anything. Recall the Countess’ failed effort to restore Marie’s good name earlier. Yet this suggestion is far from random in terms of the play’s theme. Roman Graf contends that “the notion of prostitution functions as the dominant force in male-female relation-ships throughout the play.”7 In all of the subplots the officers are preoccupied with sex, not love. And what has misled Marie and Wesener is their high regard for social station, which has stripped Marie of her identity and put her on the streets.

Clearly, Lenz designed this final scene to generate discussion among the audience, who were meant to dismiss the Colonel’s solution and provide one of their own. Lenz’s strategy was that of the Socratic teacher or parent who feigns ignorance because he wants to entice the pupil or child into showing what they have learned. Unfortunately, over the years this open ending has confounded literal-minded critics and adaptors. What did Lenz intend to be the lasting effect of his play? Bruce Kieffer points out that Lenz’s essay on the subject, the reform proposal “Uber die Soldatenehen” (“On a Married Soldiery”) makes no mention of military prostitutes, but instead proposes conventional marriage for soldiers.8 Helga Madland sees Lenz’s idealistic side in this essay, “the skepticism of his plays replaced by a messianic fervor, by devout faith in the individual and in the power of the family as society’s moral nucleus.” In “Soldatenehen” Lenz details his plan for a married soldier/citizen that would follow the model established in ancient Greece.9 Contrary to the play, whose sympathies are with women like Marie, Madland has written that the proposal depicts soldiers as “miserable collections of unhappy men, who for the most part were recruited while intoxicated, and who regretted joining the military as soon as they woke up from their stupor the next morning.”10 By reading the essay against the play, one can surmise what does not come across from the play alone: Lenz’s goal for a humane treatment of the military that would ensure their more responsible behavior toward the civilian population, especially toward women.

About Mother Courage, Brecht believed that even though Courage learns nothing, as cited in “Spectator Effect,” the audience can learn from observing her. But what are Brecht’s spectators, the children of the scientific age, to learn in such a complicated play, disunified in approach and ambiguous in its thematic presentation? Brecht wrote that a performance of Mother Courage and Her Children is primarily meant to show:

That in wartime big business is not conducted by small people. That war is a continuation of business by other means, making the human virtues fatal even to those who exercise them. That no sacrifice is too great for the struggle against war.11

This detached thematic overview doesn’t mention motherhood or a family trying to survive during a horrific war that set central Europe back more than two centuries. Compare it with how Mother Courage herself describes the play in Scene Six. She says: “All I’m after is get myself and children through all this with my cart.” (p. 57) She offers the wartime insight: “whenever there’s a load of special virtues around it means something stinks.” (p. 18) Compellingly, the central character comprehends the play’s theme and yet isn’t helped by this knowledge. That war is hell for the little people is an axiom as old as human history. And the insight that the brave, the honest, and the kind are the easy casualties of war, the inverted fairy-tale lesson, undercuts the play’s complex wisdom. Mother Courage is a case of a play knowing more than its playwright. It may be also a case of Brecht the borrower not fully gleaning everything he borrowed.

In both The Soldiers and Mother Courage the lust for profit not only reduces human beings to Sachen, or a state of thingness, but also it undermines the most fundamental human relationship, the parent and child. From the opening scene of Mother Courage this relationship is trumped by a credo of greed. The craving for material possession, the domain of comedy, is explored in both plays with tragic results. Courage’s haggling over the ransom of Swiss Cheese is a radicalization of Wesener’s playing with his daughter’s fate. By the end of The Soldiers Wesener literally doesn’t recognize Marie begging for alms, and by the end of Scene Three Courage, for her survival, must not identify her son’s body. She is given three chances to say she knows Swiss Cheese and does not, another reference to Peter’s denial of Christ. The motif of parent not recognizing a child, whether through social blindness, as in Lenz, or for survival, as in Brecht, suggests deformity in the social order that impacts even the most basic relationship. Yet, running against this pattern, Kattrin is a positive mother figure who recognizes children (though not her own), and seeks to protect them throughout the play. In Scene Eleven, the drum scene, rather than the distant drum roll of Swiss Cheese’s offstage death, the onstage Kattrin is the beater of the drum, an activist, anti-war hero, a living figure of courage at the time of her death. Her martyr’s death for the children of Halle is the play’s answer to Courage’s denial of Swiss Cheese, her decision not to identify his body. Whether or not Brecht consciously intended it, Kattrin’s motherly recognition in Scene Eleven is a thematic foil to Courage. It parallels Wesener first seeing Marie as a prostitute and then, only after feeling for her as a human being, seeing her as his daughter.

After the 1941 Zurich and the 1949 Berlin productions, Brecht was forced to acknowledge the emotional effect his play had on audiences. The Zurich audience saw Courage as a representative of the eternally suffering mother figure. She confirmed “the petty-bourgeois spectator’s confidence in his own indestructibility, his power of survival.”12 At first this bothered the playwright but after productions in Berlin and Munich, he seemed more resigned to audience misinterpretation:

Deep-seated habits lead theatre audiences to pick on the characters’ more emotional utterances and forget all the rest. Business deals are accepted with the same boredom as descriptions of landscapes in a novel. The “business atmosphere” is simply the air we breathe and pay no attention to.13

Brecht considered inserting an overtly communistic ending to the play in order to make his theme explicit, but rejected the idea for the same reason Lenz didn’t conclude The Soldiers with his ideas for a married soldiery. Both cared too much for their plays to introduce explicit moralizing or to prove philosophical points; both understood that overt pedagogy would destroy their dramatic achievements. For his part, Brecht under-estimated the power of identification that he evoked in Mother Courage. As Martin Esslin puts it:

Behind the rigid sociological framework the human side constantly reasserted itself: while the politician in Brecht piled on the social villainy, the poet in him drew on the subconscious feeling he had for the archetypal mother-figure, on his fund of pity.14

Regarding this point, Bentley has written: “And failing to notice the inescapability of identifications, he himself makes them only unconsciously. Indeed his unconscious identification with his supposed enemies becomes a source of unintended drama.”15

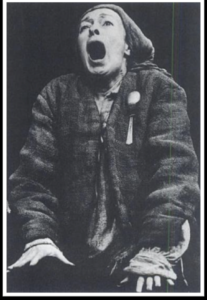

Of course not every spectator responds emotionally to the play. Iris Smith has written that Mother Courage does not engage the feminist spectator because of the stunted sexual identity of the maternal protagonist. Smith sees the play as “a traditional, perhaps even essentialist, mother/whore dichotomy that the ongoing dialectics of presentation has failed to address.”16 Sometimes emotional identification extends beyond the characters alone. In the Performance Group’s production of Mother Courage in 1975, for instance, the director replaced Courage’s wagon with “a store on the west wall of the garage.” He did this to offset the association of wagons in America with pioneers.17 The wagon does connote, I think, a different meaning for New World audiences than it does in Germany. During The Public Theater’s 2006 Mother Courage at the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park, the New York audience clearly sympathized with Meryl Streep’s Courage, a mother figure with pioneer spirit. An unexpected and important feature of the performance I saw was a long cold rain that fell on the performers and audience alike. Collective defiance of the wet weather inspired an intimacy among the audience and an empathy, even love, for the indomitable Courage played by Streep, which contrasted sharply with Brecht’s thematic intent.

Another example of a staging of Mother Courage that reflects a more modern approach to audience reception, an “instance of how the struggle has been successfully waged to free Brecht from the burden of his own models,” in Marc Silberman’s words, is the East German director Heinz-Uwe Haus’s 1977 production at the National Theatre in Weimar.18 Haus worked with a group of Chilean exiles and rejected an approach that stressed the play’s anti-war and historical aspects in favor of stressing its fragmentation of the nuclear family:

a family drama in which the idyll of familial unity and interdependence was constantly undermined by the opportunism of these little people. In other words, war became secondary to the problem of how a social microcosm, the family, generates attitudes of possessiveness and self interest.19

An approach like Haus’ points up the link between Brecht and Lenz. Brecht intended his play to be revolutionary and uncompromising in its attacks on wartime capitalism, yet Mother Courage and her Children in production compares closely with Lenz’s milder intentions in The Soldiers, which presses its audience to assess itself, learn about itself, and work toward greater cooperation, both as social beings and family members. The plays resemble each other in terms of subject, genre, character, and structure—and converge in theme as well, stressing the disastrous impact of mercantilism on the parent-child relationship.

What is truly enduring in both of these plays, however, is the striving of the central characters, their “busy-ness” not their business, their trial and error. In his essay “Opinions of a Layman” of 1775, Lenz argues against any “resting point” for a finite being. He disqualifies moral ideals as requiring a “static objective,” which contradicts the purpose of existence:

A finite being, whose whole existence is striving, whose striving never slackens, however much he may try to suppress it, until this heavenly flame is put out that makes him strive, that through endeavour makes his whole body, his whole machine sensitive, capable of enjoying the happiness he strives after, and that sinks back into its earlier insensitiveness, its earlier indolence, if this striving slackens . . .20

Striving is also the means by which Goethe’s Faust escapes damnation and Streben is critical to the theme of Faust, completed only weeks before Goethe’s death in 1832. In the closing pages of Faust II, the Angels reveal: “Whoever strives with all his power/ We are allowed to save.”21 For Marie and Courage no religious salvation is suggested, but it is their struggle from a state of dependence toward an unreachable independence, children endlessly playing games who nevertheless hope to become adults, that stays with audiences. In this way Marie and Courage both defeat inaction, Lenz’s passive condition of “only death delayed,” and succeed through their energy and movements in confirming his declaration: “Action is the soul of the world.”22

Notes

- Herbert Blau, “The Thin, Thin Crust and the Colophon of Doubt: The Audience in Brecht,” New Literary History, 21, 1, Author/Critic, Critic/Author (Autumn, 1989): 178.

- Lenz, “Review,” 204.

- Lenz, “Letters on the Morality of The Sorrows of Young Werther, Second Letter,” 198.

- Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, see Note on 229-230.

- Pope, Holy Fool, 150.

- Lenz, The Soldiers, trans. Robert David MacDonald, Three Plays (London: Oberlin Books Limited, 1993), 74. For this important stage direction MacDonald’s translation is more literal than Yuill’s.

- Graf, “Male Homosocial Desire,”36.

- Kieffer, 80.

- Madland, Image and Text (Amsterdam-Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, 1994), 100.

- Madland, Image and Text, 101.

- Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, 220.

- Brecht, 221.

- Brecht, 220-221.

- Esslin, Choice of Evils, 209.

- Bentley, Life of the Drama, 161-162.

- Iris Smith, “Brecht and the Mothers of Epic Theater,” Theatre Journal, 43. 4 (Dec., 1991): 495-496.

- Paul Ryder Ryan, “Brecht’s Mother Courage,” The Drama Review: TDR, 19.2., Political Theatre Issue (June, 1975): 78-93.

- Marc Silberman, “Recent Brecht Reception in East Germany,” Theatre Journal, 32.1 (Mar., 1980): 100.

- Silberman, “Recent Brecht Reception,” 100.

- quoted in Pascal, 124.

- Goethe, Faust, 493.

- Lenz, “On Götz,” 193.

Bibliography for Series

Anderson, William S., Barbarian Play: Plautus’ Roman Comedy, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

Bentley, Eric, “Introduction,” Bertolt Brecht–Three Plays: Baal, A Man’s a Man, The Elephant Calf, New York: Grove Press, 1964.

Bentley, Eric, The Brecht Commentaries, New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1981.

Bentley, Eric, The Life of the Drama, New York: Applause Theater Books, 1964

Blau, Herbert, “The Thin, Thin Crust and the Colophon of Doubt: The Audience in Brecht,” New Literary History, 21, 1, Author/Critic, Critic/Author (Autumn,1989): 175-197.

Boyle, Nicholas, Goethe: The Poet and the Age, Volume I, Oxford: Clarendon Press,1991.

Brecht, Bertolt, Bertolt Brecht: Poems 1913-1956, eds. John Willet and Ralph Manheim, New York: Eyre Methuen, Ltd., 1976.

Brecht, Bertolt, Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, ed. and trans. John Willett, New York: Hill and Wang, 1957.

Brecht, Bertolt, Journals: 1934-1935, eds. John Willett and Ralph Manheim, New York: Routledge/Theatre Arts Books, 1996.

Brecht, Bertolt, Mother Courage and Her Children, trans. John Willet, New York: Arcade Publishing, 1994.

Büchner, Georg, Georg Büchner: Complete Plays, Lenz and Other Writings, trans. John Reddick, London: Penguin Books, Ltd., 1993.

Chamberlain, Timothy J., ed., Eighteenth Century German Criticism: Herder, Lenz, Lessing, and others, The German Library Volume 11, New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1992.

Diffey, Norman R., “Language and Liberation in Lenz,” Space to Act: The Theater of M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Duncan, Bruce, “The Comic Structure of Lenz’s Die Soldaten,” MLN, 91, 3, German Issue, (Johns Hopkins University Press: April 1976): 515-523.

Esslin, Martin, Brecht: A Choice of Evils, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1959.

Esslin, Martin, “Brecht’s Language and Its Sources,” Brecht: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed., Peter Demetz, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1962, 171-182.

Ewen, Frederic, Bertolt Brecht: his Life, his Art, and his Times, New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1992.

Friedenthal, Richard, Goethe: His Life and Times, Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, 1963.

Fuegi, John, Bertolt Brecht: Chaos According to Plan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987.

Gilman, Richard, The Making of Modern Drama: A Study of Büchner, Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, Pirandello, Brecht, Beckett, Handke, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974.

Goethe Johann Wolfgang von, Faust, trans. Walter Kaufman, New York: Doubleday &Company, Inc., 1961.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Goethe’s Autobiography, translated by R. O. Moon, Washington D.C.: Public Affairs, 1949.

Grimm, Reinhold, “The Descent of Hero into Fame: Büchner’s Woyzeck and his Relatives,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Grimmelshausen, Johann, The Life of Courage: The notorious Thief, Whore, and Vagabond, trans. Mike Mitchell, Sawtry, Cambs, UK: Dedalus Ltd., 2001.

Guthrie, John, “Lenz’s Style of Comedy,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Herzfeld-Sander, Margaret ed., Essays on German Theatre: Lessing, Brecht, Dürrenmatt, and others, The German Library Volume 83, New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1985.

Hill, Claude, Bertolt Brecht, G. K. Hall & CO., Boston, 1975.

Hill, David, “The Rhetoric of Freedom in the Sturm and Drang,” in Literature of the Sturm und Drang, ed. David Hill, Rochester: Camden House, 2003, 159-186.

Jameson, Fredric, Brecht and Method, London: Verso, 1998.

Kes-Costa, Barbara R., “Freundschaft geht über Natur: On Lenz’s Rediscovered Adaptation of Plautus,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Kieffer, Bruce, The Storm and Stress of Language: Linguistic Catastrophe in the Early Works of Goethe, Lenz, Klinger, and Schiller, University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986.

Kistler, Mark O., Drama of the Storm and Stress, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1969.

Kitching, Laurence P. A., Der Hofmeister: A Critical Analysis of Bertolt Brecht’s Adaptation of Jacob Michael Reinhold Lenz’s Drama, München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1976.

Leidner, Alan C, and Wurst, Karin A, Unpopular Virtues: The Critical Reception of J.M.R. Lenz, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1999.

Leidner, Alan C, and Madland, Helga S, eds., Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Leidner, Alan C., ed., Sturm Und Drang: Lenz, Wagner, Klinger, and Schiller, The German Library Volume 14, New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1992.

Leidner, Alan C., The Impatient Muse: Germany and the Sturm und Drang, Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Lenz, J. M. R., Lenz: Three Plays, London: Oberlin Books Limited, 1993.

Lenz, J. M. R., J. M. R. Lenz: The Tutor/The Soldiers, trans.William E. Yuill, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1972.

Lenz, J. M. R., Sturm und Drang: The Soldiers, The Childmurderess, Storm and Stress, and The Robbers, The German Library Volume 14, ed., Alan C. Leidner, trans. William E. Yuill, New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1992.

Lewes, George Henry, The Life of Goethe, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1965.

Madland, Helga Stipa, “Gesture as Evidence of Language Skepticism in Lenz’s der Hofmeister and die Soldaten,” The German Quarterly, 57.4 (Autumn 1984): 546-557.

Madland, Helga Stipa, Non-Aristotelian Drama in Eighteenth Century Germany and its Modernity: J.M.R. Lenz, Berne and Frankfurt: Peter Lang, Ltd, 1982.

Madland, Helga Stipa, Image and Text: J.M.R. Lenz, Amsterdam-Atlanta, GA: Rodopi,1994.

Mason, Eudo C., Goethe’s Faust: Its Genesis and Purport, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. McBride, Patricia, Patricia C. McBride, “The Paradox of Aesthetic Discourse: J.M.R. Lenz’s Anmerkungen übers Theater,” German Studies Review 22, 3 (October 1999): 397-419.

Menke, Timm, “The Reception of Lenz in the Final Years of the German Democratic Republic: Christoph Hein’s Adaptation of Der neue Menoza,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

O’Regan, Brigitta, Self and Existence: J.M.R. Lenz’s Subjective Point of View, New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1994.

Osborne, John, “Anti-Aristotelian Drama from Lenz to Wedekind,” The German Theatre, Ronald Hayman, Oswald Wolff Ltd.: London, England, 1975.

Osborne, John, J. M. R. Lenz: The Renunciation of Heroism, Göttengen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Reprecht, 1973.

Pascal, Roy, The German Sturm und Drang, Manchester: Manchester University Press,

Patterson, Michael, “The Theater Practice of the Sturm und Drang,” In Literature of the Sturm und Drang, ed. David Hill, Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2003, 141-159.

Plautus, Titus Maccius, Plautus: The Darker Comedies, trans. James Tatum, Ithica, New York: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Plautus, Titus Maccius, Plautus: Three Comedies, trans. Peter L. Smith, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

Pope, Timothy, The Holy Fool: Christian Faith and Theology in J.M.R. Lenz, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Rector, Martin, “Seven Theses on the Problem of Action in Lenz,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Richardson, Horst, “Plays from German-Speaking Countries on American University Stages 1973-1988,” Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German, 23, 1 (Spring, 1990): 76-79.

Ryan, Paul Ryder, “Brecht’s Mother Courage,” The Drama Review: TDR, 19, 2, Political Theatre Issue (June, 1975): 78-93.

Schiller, Friedrich, The Robbers and Wallenstein, trans. F. J. Lamport, London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1979.

Schiller, Friedrich: “The Stage as a Moral Institution,” In Theatre Theory Theatre: The Major Critical Texts rom Aristotle and Zeami to Soyinka and Havel, ed. Daniel Gerould, New York: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2000.

Segal, Erich, Roman Laughter: The Comedy of Plautus, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Silberman, Marc, “Recent Brecht Reception in East Germany,” Theatre Journal, 32.1 (Mar., 1980): 95-105.

Smith, Iris, “Brecht and the Mothers of Epic Theatre,” Theatre Journal, 43, 4 (Dec.,1991): 491-505.

Spalter, Max, Brecht’s Tradition, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1967.

Unger, Thorsten, “Contingent Spheres of Action: The Category of Action in Lenz’s Anthropology and Theory of Drama,” Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

Waterhouse, Betty Senk, trans., Five Plays of the Sturm und Drang, London: University Press of America, 1986.

Wedekind, Frank, The Lulu Plays and Other Sex Tragedies, trans. Stephen Spender, London: John Calder Ltd., 1977.

Willet, John, Brecht: In Context, London and New York: Methuen London Ltd., 1984.

Wurst, Karin A., “A Shattered Mirror: Lenz’s Concept of Mimesis,” in Space to Act: The Theater of J. M. R. Lenz, eds. Alan C. Leidner and Helga S. Madland, Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House, 1993.

I have found this series extremely interesting and helpful! I am actually currently working a dissertation dealing with Lenz and Brecht. I am wondering if there is anyway to get access to your Master’s research? I find your argument very compelling!