Chekhov and Temporal Complexity in THE CHERRY ORCHARD

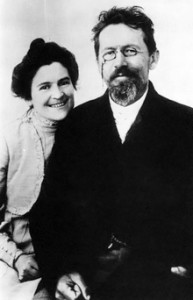

On July 2, 1904, Olga Knipper summoned a doctor to the hotel in the German spa of Badenweiler for her famous husband who was dying. After arriving, the doctor ordered champagne from room service for Chekhov. The champagne was to relieve his breathing. Olga reports that he sat up in bed and said in German, “Ich sterbe” [I’m dying]. . . “Then he picked up the glass, turned to me, smiled his wonderful smile and said: ‘It’s been a long time since I’ve had champagne.’ He drank it all to the last drop, quietly lay on his left side and was soon silent forever.”

Even with his last words, he was gauging the experience of drinking champagne in a larger context. A long time since. Chekhov was twenty-four when he first became aware of blood coming up from his throat. For twenty years slowly gave way to tuberculosis. During this time he steadfastly downplayed his condition to family and friends. He refused to be seen as a patient. As the author of THE CHERRY ORCHARD, his last completed play, Chekhov immersed the world in the temporal complexity that genius and a life long courting death had made possible.

Donald Rayfield in The Cherry Orchard: Catastrophe and Comedy has written that the subject of the play had a germination that goes back to Chekhov’s childhood. The author spent holidays in the Ukraine among a cherry orchard on a farm. Important too was the deforestation of Russia in the 1880s. And Chekhov himself owned a cherry orchard that was chopped down in 1899 by a timber dealer. Clearly the long-term biographical association of cherry orchards for Anton is important to the construction of his final play.

The Most Shocking Line in the Play

Lopakhin opens the play. It is he that provides the sense of urgency, who must convince the audience of the direness of the situation. He must do this even if Liubov Ranevskaya is unable to give the selling of the estate her full attention. The stage directions ask for him to check his watch frequently. He gives the terrible, impending date of the sale twice specifically (August 23). He refers to it more generally often: “Time will not stand still.” In this regard, Lopakhin is prepared to embrace the portentous future.

Yet, his personal shame at having come from peasantry (“Like a pig in a pastry shop”) and his unease with the advancing new political order indicate that he is stuck in the mud of his private history as much as the other characters are in their own. His hands hang at his sides as if they belong to someone else. By the end of the play when he fails to propose to Varya (fails to ask for her hand), even though this marriage proposal has long been anticipated by Varya and her mother Ranevskaya, we the audience understand that for Lopakhin the conundrum of love and marriage to the adopted daughter of an aristocratic family is as difficult to face as the sale of the cherry orchard has been for the others.

Still, it is Lopakhin that delivers the most shocking line in the play: “The cherry orchard is now mine!” It is a bald statement of a present fact that Chekhov jolts us with. This announcement is like no other statement for its power and immediacy. It leaps off the page. Chekhov has prepared for it by constructing a rich temporal world where talk of the past and future has dominated.

Tragic Heroine in a Comedy

Ranevskaya’s refusal to act exasperates us to the point of understanding it. She is no more capable of living in a world where her land is turned into plots for summer cottages (to be leased) than the new owner of the cherry orchard is capable of proposing marriage. Her story of doomed love to the “wild man” in Paris comes across as the last gasp of the heroic notion of tragedy in an increasingly pragmatic middle-class world. That her husband died from drinking champagne suggests that he deemed every minute worthy of celebration. That her son drowned in the river on the estate underscores the flow of time, river as nature’s counterpoint to humankind’s railroad.

When the fateful day of the auction has arrived, Ranevskaya says: “It was the wrong time to have the musicians, the wrong time to give a dance . . . Well, never mind . . .”

Her brother Gayev says of her: “She is good, kind, charming, and I love her dearly, but no matter how much you allow for extenuating circumstances, you must admit she lives a sinful life. You feel it in her slightest movement.” The daughter Anya hears this and gently but firmly makes her uncle retract it. Gayev admits it was a stupid (bourgeois?) thing to say. He admonishes himself for being the kind of person who makes speeches to bookcases and muses over the passage of time. “There was a time, sister, when you and I used to sleep here in this very room, and now I’m fifty-one, strange as it may seem.”

Orphaned in Time

The governess Charlotta says, “I haven’t got a real passport, I don’t know how old I am, but it always seems to me that I am quite young.” She goes on to say that she doesn’t know whom her parents are, that she doesn’t know anything—her age, her ancestry. Charlotta is completely orphaned in time like a character in an absurdist play. (Beckett who admired THE CHERRY ORCHARD must have read the lines of Charlotta with interest.)

Yepikhodov the clerk says that he doesn’t know his own inclinations and doesn’t know “what it is I really want, whether, strictly speaking, to live or to shoot myself.” He says he always carries a revolver with him and shows the revolver. Despite being well read, Yepikhodov lives in a kind of personal void, without faith in anything.

That the gun never goes off and that Lopakhin doesn’t pop the question, these two “non-actions”, are Chekhov’s sagely counterbalance to the sale of the estate. He shows, quite remarkably, that THE CHERRY ORCHARD is neither a tragedy that will end with a gunshot nor a comedy ending in a marriage, but something entirely different.

As a character who seems aware of the changing times and offers a contrasting view to Lopakhin’s capitalism, Trofimov makes proletariat speechs that seem to presage the coming revolution in 1905. At the end of his first speech about humankind, he says, “We should stop admiring ourselves. We should work and that’s all.” But Chekov in his plays and fiction is ambiguous about revolution, a fact that angered those Russian intellectuals who wanted their great writers to provoke unrest.

Trofimov stops short of being a revolutionary. “I’m afraid of serious conversations,” he says. “We do better to remain silent.” And what he says about he and Anya, “We are above love,” puts him into conflict with Ranevskaya. He goes to far when he attacks her true love in Paris as a “scoundrel” and “nonentity.” Ranevskaya proves fierce when defending what is important to her, her love. “It’s not purity with you, it’s simple prudery, you’re a ridiculous crank, a freak—”

Please Stop Until She’s Gone

Just as THE CHERRY ORCHARD begins with the arrival of a train, the last act is a countdown for Ranevskaya and her family to catch the departing train. The play exists between the arrival and departure on time’s arrow. When the stage directions call for the sound of trees being chopped in the distance, it is, indeed, a terrible and melancholy sound. As audience we can’t help remind ourselves of all we’ve experienced with the characters, and the dying of an age, that in the trees are generations of souls from the peasants who worked the fields. Trofimov says, “Don’t you see that from every cherry tree, from every leaf and trunk, human beings are peering out at you.”

To me the most poignant line in the play is the seventeen-year-old Anya’s when she says to Lopakhin soon after the chopping has started: “Mama asks you to stop cutting down the cherry orchard until she’s gone.” Though THE CHERRY ORCHARD is categorized as a “Comedy in Four Acts” and functions as a comedy with sadness, this request for leniency, for a few more minutes without the sound of ax colliding with wood, is about as sorrowful as a play can get.

For my thoughts on the sound of the breaking string in the stage directions, please see my first post on CHERRY ORCHARD.

Leave a Reply